How a simple mix of object-oriented programming can sharpen your deep learning prototype

By mixing simple concepts of object-oriented programming, like functionalization and class inheritance, you can add immense value to a deep learning prototyping code.

Introduction

This post is not meant for seasoned software engineers. This is geared towards data scientists and machine learning (ML) practitioners, who like me, do not come from a software engineering background.

We use Python a lot for our work. Why? Because it’s awesome for ML and data science community.

It is on the way to becoming the fastest growing major language for modern data-driven analytics and artificial intelligence (AI) apps.

However, it is also used for simple scripting purpose, to automate stuff, to test a hypothesis, create interactive plots for brainstorming, to control lab instruments, etc.

But here is the thing.

Python for software development and Python for scripting is not exactly the same beast — at least in the domain of data science.

Scripting is (mostly) the code you write for yourself. Software is the assemblage of code you (and other teammates) write for others.

It will be wise to admit that, when (a majority of) data scientists, who do not come from a software engineering background, write Python programs for AI/Ml models and statistical analysis, they tend to write such code for themselves.

They just want to get to the heart of the pattern, hidden in the data. Fast. Without thinking deeply about normal mortals - users.

They write a block of code to produce a rich and beautiful plot. But they don’t create a function out of it, to use later.

They import lots of methods and classes from standard libraries. But they don’t create a subclass of their own by inheritance and add methods to it for extending the functionality.

Functions, inheritance, methods, classes — these are at the heart of robust object-oriented programming (OOP), but they are somewhat avoidable if all you want to do is to create a Jupyter notebook with your data analysis and plots.

You can avoid the initial pain of using OOP principles, but that, almost always, renders your Notebook code non-reusable and non-extensible.

In short, that piece of code serves only you (until you forget what logic exactly you coded) and no one else.

But readability (and thereby re-useability) is critically important. That is the true test of the merit of what you produced. Not for yourself. But for others.

In fact, data scientist Will Koehrsen just wrote a wonderful piece on this idea.

Notes on Software Construction from Code Complete

Lessons from “Code Complete: A Practical Handbook of Software Constructions” with applications for data science

To top it off, the hundreds of popular MOOC or online courses on data science and AI/ML also do not emphasize this aspect of coding, because it feels like a burden for a young, enthusiastic learner. He/She is here to learn cool algorithms and neural network optimizations, not OOP in Python. Consequently, this aspect remains neglected.

So, what can you do?

A simple mix of OOP can sharpen your deep learning (DL) code

I am not a software engineer, never had been in my life. So, when I started exploring ML and data science, I wrote a great many amounts of sloppy, non-reusable code.

Gradually, I am trying to become better and using simple enhancements to my coding style to make them more useful (for anybody in the world).

And, I have discovered that it does not take much to start mixing OOP principles in your data science code.

Even if you never took a software engineering course in your life, some ideas may come naturally to you. All you have to do is to put yourself in someone else’s shoe and think about how that person will take and use your code in a constructive manner.

- If you have a code block that appears more than once in your analysis (in the exact same form or in slight variations), can you make a function out of it?

- When you make such a function, what parameters will be passing on? Which one of them can be optional? What will be the default values?

- If you encounter a situation where you don’t know how many parameters will need to be passed on, are you using the *args, **kwargs that Python offers?

- Did you write a docstring for that function to let others know what the function does and what parameters it expects, an example perhaps?

- When you have collected a bunch of such utility functions, are you still working on the same notebook, or switching over to a new, clean notebook and just calling “from my_utility_script import func1, func2, func3” (Did you create a my_utility_script as a simple Python file rather than a Jupyter notebook)?

- Did you put the my_utility_script in a directory, put an __init__.py file (even a blank one) in the same directory and make it a Python moduleto be importable just like NumPy or Pandas?

- Are you thinking about not merely importing classes and methods from great packages like NumPy and TensorFlow but adding your own methods to them and extending their functionality?

What do I even mean by all of these? Let’s demonstrate using a simple case — a DL image classification problem with the fashion MNIST dataset.

Case illustration with a DL classification task:

The approach

The detailed notebook is given here in my Github repo. You are encouraged to go through it and fork it for your own use and extension.

Code is essential for building great software but not necessarily suitable for a Medium article, which you are reading to gain insights, and not practicing a debugging or refactoring exercise.

Therefore, I will just pick up chosen code snippets and try to point out how I tried to encode some of the principles, detailed earlier, in this Notebook.

The core ML task and the higher-order business problem

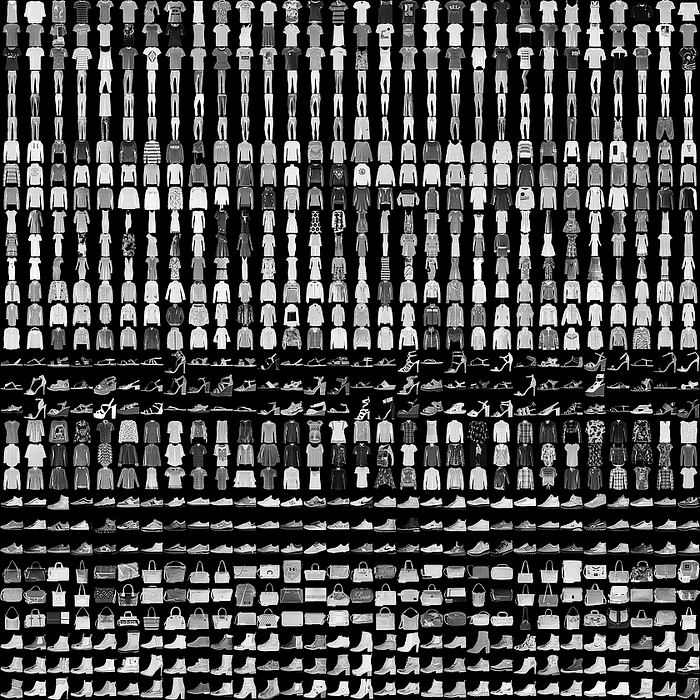

The core ML task is simple — building a deep learning classifier for the fashion MNIST dataset, which is a fun spin on the original famous MNIST hand-written digit dataset. Fashion MNIST consists of 60,000 training images of 28 x 28 pixel size — of objects related to fashion e.g. hat, shoe, trouser, t-shirt, dresses, etc. It also consists of 10,000 test images for model validation and testing.

But what if there is a higher-order optimization or visual analytics question around this core ML task —how the model architecture complexity impacts the minimum epochs it takes to reach the desired accuracy?

It should be clear to the reader, why we even bother about such a question. Because this is related to the overall business optimization. Training a neural net is not a trivial computational matter. Therefore, it makes sense to investigate what minimum training effort must be spent to achieve a target performance metric and how the choice of architecture impacts that.

In this example, we will not even use a convolutional net, as a simple densely connected neural net can accomplish reasonably high accuracy, and, in fact, a somewhat sub-optimal performance is required to illustrate the main point of the higher-order optimization question we posed above.

Our solution

So, we have to solve two problems -

- How to determine what the minimum number of epochs is for reaching the desired accuracy target?

- How the specific architecture of the model impacts this number or training behavior?

To achieve the goals, we will use two simple OOP principles,

- Creating an inherited class from a base class object

- Create utility functions and call them from a compact code block which can be presented to an external user for higher order optimization and analytics

Code snippets to show the good practices

Here we show some code snippets to illustrate how simple OOP principles have been utilized to achieve our solution. The snippets are marked with comments for easy understanding.

First, we inherit a Keras class and write our own subclass adding a method for checking training accuracy and taking an action based on that value.

This simple callback results in dynamic control of the epochs — the training stops automatically when the accuracy reaches the desired threshold.

We put the Keras model construction codes in a utility function so that a model of an arbitrary number of layers and architecture (as long as they are densely connected) can be generated using simple user input in the form of some function arguments.

We can even put the compilation and training code into a utility function to use those hyperparameters in a higher-order optimization loopconveniently.

Next, it’s time for visualization. Again here, we go by the practice of functionalization. Generic plot functions take raw data as input. However, if we have a specific purpose of plotting the evolution of training set accuracy and showing how it compares to the target, then our plot function should just take the deep learning model as the input and generate the desired plot.

A typical result looks like following,

Final analytics code — super compact and simple

And, now we can take advantage of all the functions and classes, we defined earlier, and bring them all together to accomplish the higher-order task.

Consequently, our final code will be super compact but it will generate the same interesting plots of loss and accuracy over epochs, that we show above, for a variety of accuracy threshold values and neural network architectures.

This will give a user the ability to to use a minimal amount of code to produce visual analytics about the choice of performance metric (accuracy in this case), and neural network architecture. This is the first step towards building an optimized machine learning system.

We generate a few cases for investigation,

Our final analytics/optimization code is succinct and easy to follow for a high-level user, who does not need to know the complexity of Keras model building or callbacks classes.

This is the core principle behind OOP — the abstraction of the layers of complexity, which we are able to accomplish for our deep learning task.

Note, how we pass on the print_msg=False to the class instance. While we needed basic printing of status for initial check/debug, we should execute the analysis silently for the optimization task. If we did not have this argument in our class definition, then we would not have a way to stop printing debugging messages.

We show some of the representative results which are automatically generated from executing the code block above. It clearly shows, how with a minimal amount of high-level code, we are able to generate visual analytics to judge the relative performance of various neural architectures for various levels of performance metrics. This gives a user, without tweaking the lower-level functions, easily make a judgment on the choice of a model as per his/her performance demand.

Also, note the custom titles for each plot. These titles clearly enunciate the target performance and the complexity of the neural net, thereby making the analytics easy.

It was a small addition to the plotting utility function but this shows the need for careful planning while creating such functions. If we had not planned for such an argument to the function, it would not have been possible to generate a custom title for each plot. This careful planning of API (application program interface) is part and parcel of good OOP.

Finally, turn the scripts into a simple Python module

So far, you may be working with a Jupyter notebook, but you may want to turn this exercise into a neat Python module, which you can import from any time you want.

Just like you write “from matplotlib import pyplot”, you can import these utility functions (Keras model build, train, and plotting) anywhere.

Summary and conclusions

We showed some simple good practices, borrowed from OOP, to apply to a DL analysis task. Almost all of them may seem trivial to seasoned software developers but this post is for budding data scientists who may not have that background but should understand the importance of imbuing these good practices in their machine learning workflow.

At the risk of repeating myself one too many times, let me summarize the good practices, again here,

- Whenever get a chance, turn repetitive code blocks into utility functions

- Think very carefully about the API of the function i.e. what minimal set of arguments is required and how they will serve a purpose for a higher level programming task

- Don’t forget to write a docstring for a function, even if it is a one-liner description

- If you start accumulating many utility functions related to the same object, consider turning that object to a class and putting the utility functions as methods

- Extend class functionality whenever you get a chance for accomplishing complex analysis using inheritance

- Don’t stop at Jupyter notebooks. Turn them into executable scriptsand put them in a small module. Build the habit of modularizing your work so that it can be easily reused and extended by anyone, anywhere.

Who knows, you may be able to release a utility package on the Python package repository (PyPi server) when you accumulate enough of useful classes and sub-modules. You will have the bragging right of releasing an original open-source package then :-)

If you have any questions or ideas to share, please contact the author at tirthajyoti[AT]gmail.com. Also, you can check the author’s GitHub repositories for other fun code snippets in Python, R, or MATLAB and machine learning resources. If you are, like me, passionate about machine learning/data science, please feel free to add me on LinkedIn or follow me on Twitter.

Bio: Tirthajyoti Sarkar is the Senior Principal Engineer at ON Semiconductor working on Deep Learning/Machine Learning based design automation projects.

Original. Reposted with permission.

Related:

- Optimization with Python: How to make the most amount of money with the least amount of risk?

- How do you check the quality of your regression model in Python?

- Mathematical programming — Key Habit to Build Up for Advancing Data Science