“TV of tomorrow is now here.” So says The Guardian. The TV show that brought us into the future is Bandersnatch, the recently released interactive television show from the Black Mirror anthology. Bandersnatch is sort of modern reincarnation of the Choose Your Own Adventure books of your childhood. Some reviewers raved about the new experience:

"This is what Bandersnatch gave me that no other movie had ever been able to. Before you say it, I know it’s just an illusion of choice and I had no real control over what played out on screen, but it still provided me with more influence on a narrative that wasn’t my own than I’d ever had before, and I revelled in the possibilities. To me, Bandersnatch is both a movie and a game and something entirely new. It’s a lesson in human psychology, a thesis on the illusion free will, and one hell of an entertaining few hours all rolled into one. And, perhaps most importantly, it’s only the beginning.” Lauren O’Callaghan, Gamesradar

For me, my intrigue with Bandersnatch relates to its similarities with our Juicebox-created interactive data stories. I thought it was worth examining some of the technical and narrative challenges faced by this TV experiment to find lessons for data storytelling.

The very first lesson: Be careful about using the term “Choose Your Own Adventure.” Netflix is getting sued. The other lessons fall into a couple of categories: 1) functionality for interactive storytelling; 2) understanding the audience needs.

Essential Functionality for Interactive Storytelling

Netflix appreciates the necessity of teaching their audience how to use the interactive experience. From the very beginning of the show, you are confronted with the selection mechanism, even before the show begins. To validate that the audience is learning how it works, your next couple of choices are trivial ones, i.e. which type of cereal or music our character would like. These interactions build a sense of comfort before some of the more dreadful decisions arrive.

In Bandersnatch, as in most analytical exercises, it is possible to make choices that result in a dead-end to your story. For example, when our hero Stefan decides to produce his game with a game company, we quickly learn that this choice won’t result in a realization of his gaming vision. Netflix provides a quick mechanism to teach you that this was a wrong-turn and gets you back to a place in the story where you can pick a better option. Imagine the same careful handholding in an Excel PivotTable: at the moment when you choose an option that creates one of those 200 column nightmares, Excel instantly asks if you’d like to make a better choice. If only.

Perhaps Netflix’s greatest accomplishment is with their underlying technology for Bandersnatch that enables a seamless video experience. As a viewer, you make a choice and the video immediately launches you into the next chapter of the story. The same seamless flow needs to exist in data stories; make a selection, immediately see the results. It is a requirement to make users excited to explore the world you are creating.

The Challenges of Interactive Storytelling

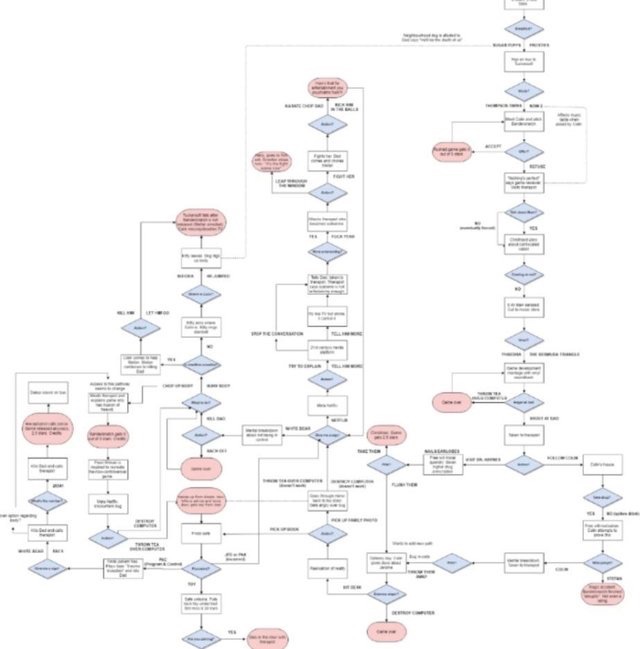

Choose Your Own Adventure-style storytelling comes with its own challenges. The author needs to define many endings. Each permutation needs to find a way to connect — all while still developing characters and themes. In fact, one theme of Bandersnatch is that the complexity of this type of storytelling may drive a person to madness. Here’s a look at the decision-tree behind the show:

What else do we need to consider in telling stories of this form?

To start, we might consider how different audiences react differently to the injection of choice into their entertainment. For every person who is intrigued by asserting more control over the story, there will be others who are looking for passive entertainment.

"Even the most complex, arresting, emotionally draining show is essentially escapism because all the work is done for us.” …do people want to be the decision makers? It is hard work.

As a viewer, I will wave from the shores of traditional TV, happy to be spoonfed my entertainment and hoping that the young folk are having fun.” — The Guardian

Secondly, we have to ask: Does choice come at the expense of characters, coherence, and clarity of story telling? Bandersnatch struggled to build interesting characters. Traditional stories control the audience’s perception of a character at all times, and therefore can build a foundation of what makes that character work, layer by layer. By ceding control of that process to the audience, the author provides a collection of character “bricks” that haven’t been constructed into anything.

"It rarely deviated from the expected deviance, rarely landed in an unexpected place or – and this was where it most resembled its videogaming ancestry – had energy to spare to make the characters much more than ciphers.” — The Guardian

Finally, the audience of an interactive story has to ask themselves (just as Stefan asks): Are we really in control of our choices, or is there a hidden power that is flipping the switches? Are we only getting the illusion of choice?

Bandersnatch is mostly satire, too, but the "gameplay" jumps around a confusing timeline, making you repeat past scenes with different decisions. How you interact with your therapist, whether you agree to take drugs, and if you manage to open a secret safe, for example, all bring you down different paths and to several Game Over screens. These soft endings then send you back to earlier scenes, so you can choose the "correct" choice to further your progress. You have to do this numerous times to eventually receive a true ending. The concept of "right" and "wrong" choices bothered me and cornered me into decisions I didn't want to pick. — Elise Favis, Game Informer

For TV, this is an evolving entertainment form. In the world of data, we are also creating an evolving communication form. How do we find the balance of choice and flexibility with message? How can we engage and entertain without heaping the burden of authorship on an audience? These are questions we’ll need to continue to explore.