Data professionals often talk about the importance of managing data and information as organizational assets, but what does this mean? What is the actual business value of data and information? How can this value be measured? How do we manage data and information as assets? These are some of the questions that I intend to address in this series of articles.

In the first part of this series, we talked about the different ways data and information can be used to create business value. The next question we need to address is: What kind of an asset is data, and how should it be managed?

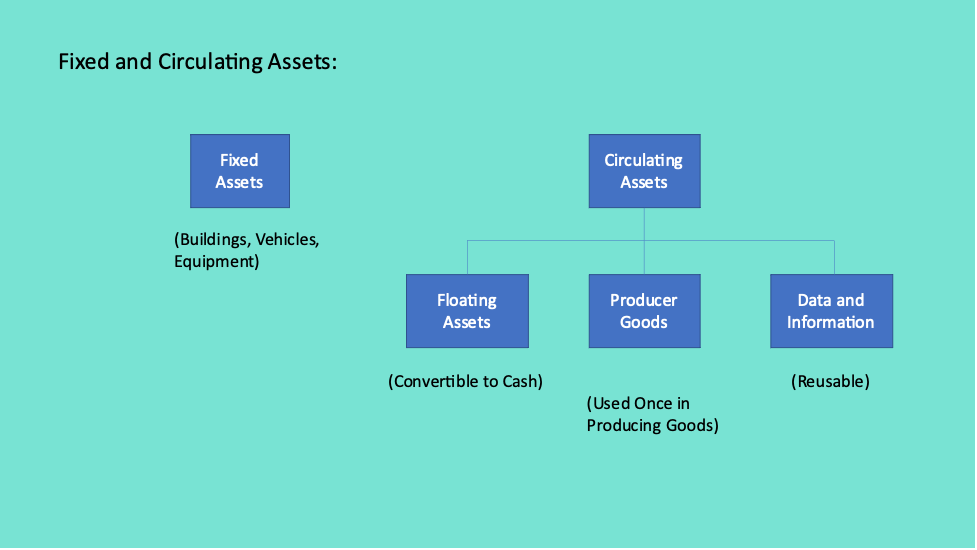

Data as a Circulating Asset

Data and information are a special type of asset called a circulating asset, as opposed to fixed assets such as buildings or vehicles. Circulating assets morph easily from one form into another (e.g., cash can be used to buy raw materials), and can be used and disposed of without having to obtain permission from, say, a creditor. There are many types of circulating assets such as floating assets (which includes cash and anything else that can easily be converted into cash), producer goods (which includes raw materials and fuel used one time in creating goods for market), and finally, data and information.

But data and information are very special types of circulating assets, with some very special properties that we need to take note of:[i]

- Data is immutable – It is not consumed as it is used and is therefore always available for additional reuse, up to the end of its useful life.

- Data is copyable – It can exist in multiple places at the same time and can be used simultaneously by multiple people.

- Data is indivisible – It must be used within a context that gives it meaning and business value. For example, what does the string of numbers “12345” mean? The answer is, it depends, and what it depends on is the context in which these numbers appear. If they appear on the odometer of a car, then they are a mileage figure. If they appear on an accounting ledger or balance sheet, then they’re probably an amount value. If they appear in the address section of an envelope, then they’re probably a zip or postal code (and, in fact, “12345” is one of the zip codes for Schenectady, New York).

- Data is accumulative – It can be combined with other data and transformed into additional data assets at will.

Another critical difference between data and other assets is that there is a “fitness for purpose” aspect to data that doesn’t exist for other assets. When you spend cash or liquidate stocks, you don’t have to ask whether they are fit for the intended purpose. With data assets, effort must be expended to ensure that their quality, timeliness and relevance qualify them for the purpose for which they are being used. The question, “Is this data good enough?”, must always be asked and answered.

These special characteristics of data give us some insight as to how data and information should be managed so as to generate value for organizations. For one thing, it means that the value of data assets is directly tied to their sharing and reuse. Data needs to be in motion, not static. It needs to be used to create “virtual value streams” of information that link organizations to their customers and other stakeholders in creative and engaging ways. Years ago, I said that most organizations do not get any significant ROI (return on investment) from their data because much of their data sits in application-specific databases or Excel spreadsheets and are only used to support one application or business function. Data and information that is not shared and reused across business units does not contribute significant value to an organization!

It also means that data and information must be managed to ensure their “fitness” for whatever purpose they are being used for. Organizations must be able to trust the quality, accuracy, timeliness, and business relevance of their data. All assets must be managed; the difference with data is that users must know enough about the data they are using (e.g., the source, quality, meaning, and timeliness of the data) to decide how to use it, and what to use it for. As mentioned above, data only has value when used within a context that gives it meaning and value.

This brings us to our third point: Because data only has meaning within a particular context, consumers of data and information need metadata to help them decide how to use it. This is an important difference between data and other assets. You don’t need much metadata when deciding whether to spend a $20 bill, but you do need metadata when trying to decide whether a given set of accounting data is fit for, say, a year-end report to shareholders, regulators, and auditors, or is only suited to be used for monthly trial balances.

It is these three aspects of data management (managing data for quality and fitness, assigning metadata/context to data, and managing data for reuse/repurpose) that transform data from mere resources to actual data assets.

One final point about asset management: Generally speaking, what is being managed is not the asset itself, but rather the behavior of stakeholders regarding that asset. We don’t manage money so much as we manage the behavior of people with regard to spending, and the reporting of their spending. An inventory manager controls when new inventory is ordered, and in what quantities. What data managers manage are the processes by which data assets are acquired, evaluated, enhanced, provisioned, used and (eventually) disposed of, in ways that ensure the maximum amount of value at least cost for the company. Asset management is never the management of things — it is always the management of people and processes.

In the next part of this series, we will explore in more detail the ways in which data must be managed to ensure its value to an organization or business.

Image used under license from Shutterstock

[i] This material is taken from Chapter 2 of my book “Growing Business Intelligence” (Technics Publications, 2016), pp. 18-20.