Those of us in the field of enterprise data management are familiar with the many authors contributing their knowledge and expertise to the data management body of knowledge.[1] We are also very familiar with the many, varied, and often conflicting ways in which data management terms are used. “Data architecture,” “data integration,” and even terms as seemingly simple as “data element” have very different meanings depending on the who, what, when, where, and why of a particular conversation.

“Data governance” is another one of those terms. A search of just TDAN.com on “data governance” returns 68 pages of articles about “data governance,” with several appearing every month. I’ve read the work of many data governance voices — the Robert Seiners and the John Ladleys — but it would be impossible for me to consume even half of what’s been written. Nevertheless, I would like to contribute my own simple view of data governance that’s both realistic and easy to understand.

Governance and Management

Governance is governance regardless of what’s being governed. Just like a good manager can manage any kind of project and a good salesman can sell any kind of product, a good governor can govern any kind of domain. In-depth knowledge of the project, product, or domain can certainly improve the effectiveness of the manager, salesman, or governor, but there are basic skills, principles and lessons learned that are “portable” and applicable across projects, products, and domains. I’m sure all of you data modelers out there say the same about data modeling: Good data modeling is the same practice regardless of domain, but knowledge of the domain helps tremendously.

It is also important to recognize that governance is not management — it is a distinct organizational function. Governance is what a Board of Directors does; management is what a CEO and managers do. A Board of Directors does not involve itself in operations; it assigns a CEO or director the responsibility to run the organization and to meet performance objectives.

The Tripartite Governance Model

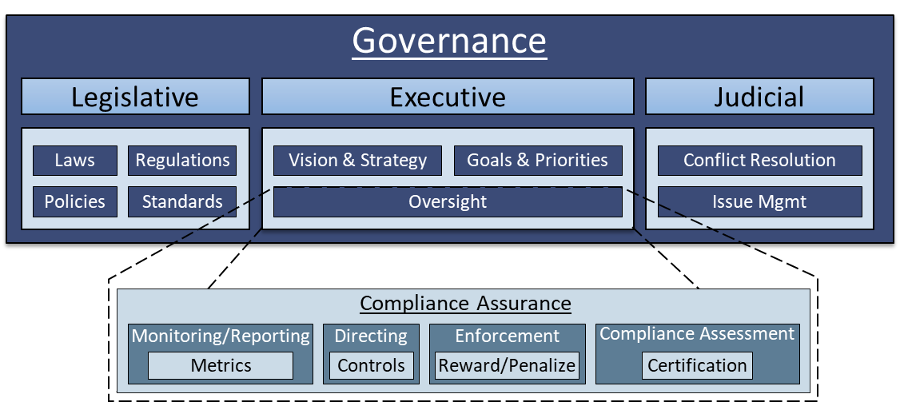

The simplest way to look at and understand the responsibilities of the governance function is the model represented by the U.S. Federal Government. The governance function is comprised of the following capabilities (Figure 1):

- Legislative: Establishing and maintaining the laws, regulations, policies, and standards that establish requirements and limit acceptable behaviors

- Executive: Providing leadership (e.g., goals, objectives, strategies) and oversight (making sure the behaviors of the governed domain meet goals and do not violate legislation)

- Judicial: Resolving conflicts and issues and deciding the “big questions”

Governance is as simple as that. And data governance is as simple as that.

The details of implementing this model are, of course, challenging and enterprise-specific. It is also where the guidance of the Robert Seiners and John Ladleys comes into play. As near as I can tell, this model is compatible with that guidance.

The 3 x 3 Governance Model

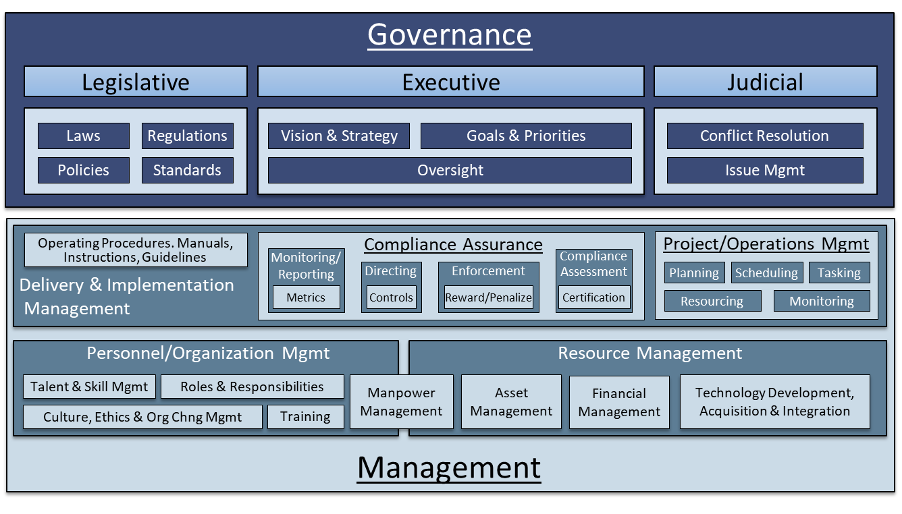

Data governance is often conflated with the operational functions of a data management organization. Operations management is what managers do: they monitor and control the day-to-day activities of the organization. This involves planning and scheduling, resource management (people, capital, and financial assets), communications, engineering and design, compliance assurance, and — ultimately — delivery. Compliance assurance is the operational function mostly directly tied to the governance function, as shown in Figure 2. Compliance assurance is a “policing” function that monitors, enforces, and assesses compliance to legislation. Reporting of compliance assurance activities provides feedback to the governing body, thus enabling oversight.

The other functions of operations management are exactly what you’d expect and exactly what comprises other models of operations management, as illustrated in Figure 3.

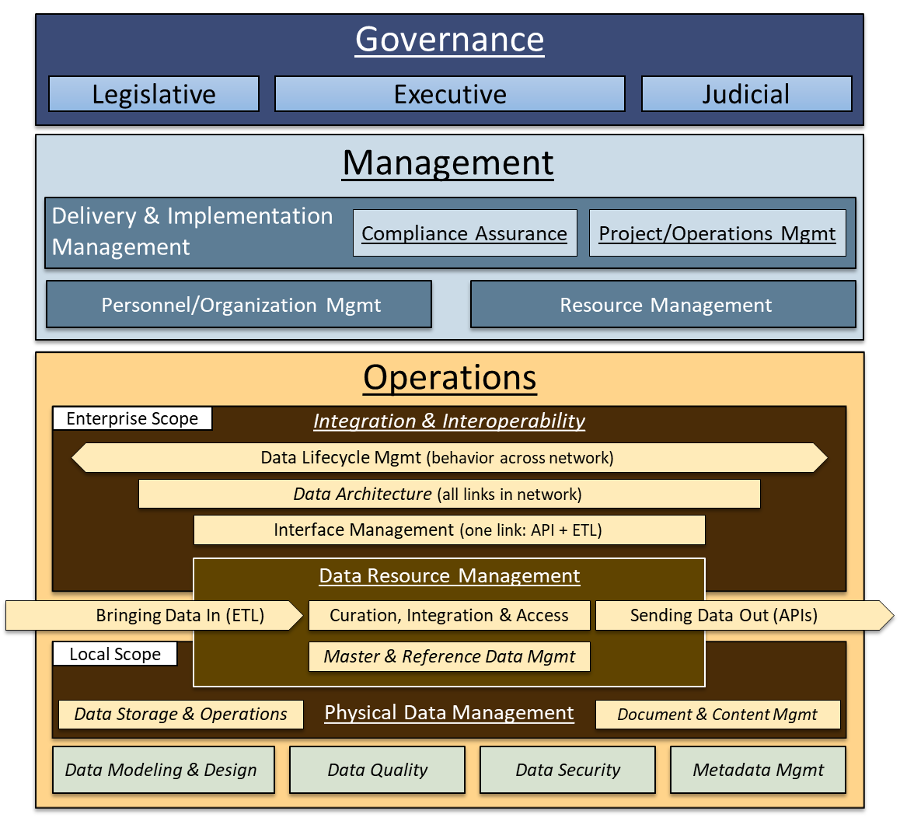

So, what does this have to do with data governance? Nothing at all, really — this is just a simple and recognizable model for managing and governing any kind of enterprise or endeavor. I have found that most extant books and articles on data governance directly address many or all of these functions, and they are contextualized as data-management-specific functions: data asset management, data standards, data compliance assessment. There’s nothing wrong with that and there are data-management-specific features and characteristics to all these functions. It’s just important to recognize that the functions are (or should be) “clicked-into” standard business management and governance functions — the functions and their interrelationships are not unique to data management.

So, what is unique to data governance and data management? The activities that are governed and managed, of course. See Figure 4.

The operational data management capabilities identified in Figure 4 largely correspond to the knowledge areas found in DAMA’s Data Management Body of Knowledge (DMBoK);[2] those in italicized text correspond to segments of the DM-BOK “knowledge wheel.”

For the purposes of this article, there is no need to consider these capabilities in any detail beyond identifying them — we all already know something about them. What is important to see, however, is that every single box (i.e., “capability”) in the model requires overt and explicit legislation to govern that capability. This includes all the governance capabilities as well!

Scoping and Scaling

The nature of the legislation depends on the scope of the governed domain. It may be tempting to establish very detailed standards for data quality, for example, but if the enterprise is large, the level of detail might not be applicable everywhere within and across the enterprise. Therefore, for the scope of a large enterprise, the right “scale” for data quality legislation may perhaps just be the simple mandate: “Thou shalt have a Data Quality Management Plan.” Subdivisions of the enterprise with smaller scopes of authority would or could then “specialize” or “extend” that mandate by specifying the structure and content of a data quality management plan that fits their local requirements.

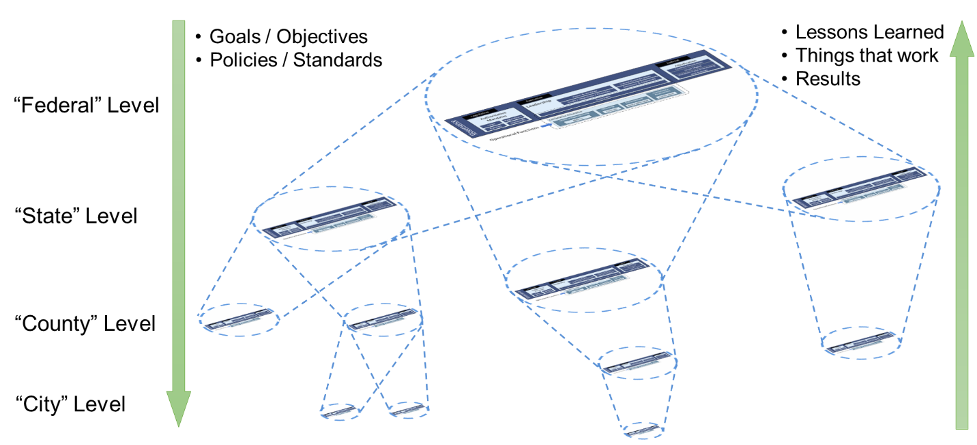

Governance scalability can be viewed in the same way civil governments, as illustrated in Figure 5. “Federal” level legislation is general and viewed more as “guardrails;” legislation for smaller domains can then establish their own more specific and detailed legislation that stays within the guardrails.

There’s an organic and evolutionary aspect to this governance structure. General policies and standards are propagated “down” to smaller domains; and lessons learned, things that work, and results are propagated “up” to inform subsequent iterations of the policies and standards. Thus, governing legislation can adapt and evolve as the enterprise evolves.

The Creeping Tent

There’s an advantage that I see in the 3 x 3 model that can help sort out and better understand the content of a lot of data management literature. I’m sure that you have seen, as I have seen, the following kinds of recommendations recurring in sooooo many articles and books for soooo many years:

- “Upper-level management buy-in and support is essential!”

- “Need to connect back to enterprise goals.”

- “Produce value for the enterprise.”

- “Start small, prove worth, and build into an enterprise-scale program.”

These themes of senior management support, proving worth, and starting small show up in books about data quality, master data management, enterprise data management, data governance — often consuming very sizable percentages of the book or article. Why is this? Because there is a failure to recognize the three lanes laid out above in the 3 x 3 model and stay in a particular lane.

I call this the Creeping Tent phenomenon. Using data quality as an example, the “long pole in the tent” is, of course, data quality. However, it’s not possible to implement and execute any kind of data quality program without considering management and governance capabilities. Therefore, the content of a data quality book or article “creeps” outward to encompass some management and governance capabilities.

I’m a modular thinker. Instead of each data quality book — and each master data management book, and each data governance book, etc. — addressing “upper-level management buy-in” and “incremental roll-out,” what I’d like to see is a single book that could be “plugged into” the books on data quality, master data management, etc. This work would address basic enterprise business program conceptualization, development, sales (to management), roll-out and implementation, governance, and management. I’m sure there are works like that already out there, but material like that isn’t on my usual reading radar and I’m unable to cite an example. If there is such a work, it could serve as an anchor and common reference for articles and books on data management subjects and free them from having to reconsider and repeat “senior-level management buy-in and support is essential” for the umpteenth time.

Last Thoughts

As stated earlier, there is a lot of great work on the subject of data governance out there, by authors with far more experience than I. My goal with this article was to reframe and offer a different, and perhaps clearer, lens with which and from which to view, understand, and implement data governance within an enterprise.

[1] The general “body of knowledge,” with nods to DAMA and the DMBoK.